The World Health Organization recommends that adults engage in at least 150 to 300 minutes of moderately intense physical activity per week, but only about a quarter of adults worldwide achieve this target (WHO, n.d.). Regular physical activity helps prevent overweight and obesity (OECD, 2019), promote human capital formation (Cappelen et al., 2017; Fricke et al., 2018) and improve memory (Erickson et al., 2011; Roig et al., 2013). While most of us know that exercise is important, many of us struggle to put our physical activity goals into practice. Even individuals who have gone as far as getting a gym membership tend to report not visiting the gym as often as they would like (Gerdtham et al., 2020).

The challenge faced, by individuals and policymakers alike, is how to get people to be more active. This is where commitment contracts come into play. Commitment contracts are tools that help individuals overcome struggles with low self-control. These contracts involve making a pledge with oneself to achieve a specific goal, and often include penalties for failing to achieve the goal. The penalties can range from a sense of personal disappointment (soft commitment) to actual financial penalties (hard commitment). While commitment contracts have been successful in various domains, such as getting people to stay sober (Schilbach, 2019), achieve academic goals (Himmler et al., 2019), and be physically active (Royer et al., 2015), it is not yet clear to what extent the hard penalties or the contracts themselves drive the behaviour change. Put simply, is it possible to achieve the same behaviour change with a contract alone, or is the hard penalty important?

To answer these questions, Spika et al. (2023) conducted a field experiment in collaboration with a large gym chain in Stockholm, Sweden. 1629 participants were randomly assigned to either a control group (no contract offer), a soft commitment contract group (contract offer only), or a hard commitment contract group (contract offer plus opportunity to add financial stakes). Participants assigned to the soft or hard contract groups were offered the opportunity to design a contract for themselves in which they set a goal number of gym visits per month over a period of one to four months. After designing the contract, those assigned to the hard contract group were given the opportunity to add a financial penalty to their contract by making a deposit of a self-chosen positive amount to the research team. In practice, the minimum deposit amount was 10 SEK and the maximum was 1000 SEK. By randomising the offer of the different kinds of contracts, we can explore whether the effect of commitment contracts differs depending on whether the contract involves a hard penalty or not.

Over 82% of participants in both treatment groups accepted a contract (soft or hard). This suggests a large demand for commitment contracts in our study population. Within the hard contract group, 41% accepted to add stakes when offered the opportunity to do so. As can be seen in Figure 1, most participants who accepted a contract designed one lasting four months and in which they committed to visit the gym 8 to 12 times per month.

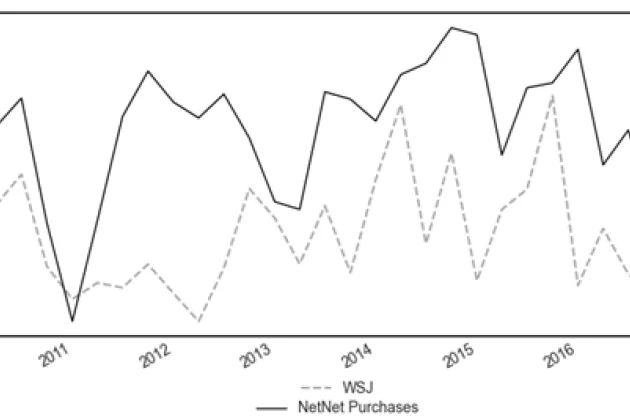

In Figure 2 we show how participant visits to the gym vary across treatment groups and months since entry into the study. Because the maximum possible (and most popular) contract length was four months, we split the observation period into an “experimental” period consisting of months one to four, and a “post-experimental” period consisting of months five to eight. We find that, during the experimental period, individuals in the hard contract group visit the gym approximately 21% more often than those in the control group, while those in the soft contract group visit the gym approximately 8% more. Overall, we find that the probability that those offered a hard contract meet their contract goal is approximately 20%, which is about 5% higher than the probability among those offered a soft contract.

As one might expect, participants with relatively low self-control were more likely to accept the contract offer. The effects of soft and hard contracts did not, however, depend on the level of self-control. A striking finding, seen in Figure 3, is that the effects of both hard and soft contracts were greatest among participants with the lowest activity levels prior to the experiment, and this effect persists even after the contract ends.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to experimentally compare the effectiveness of both soft and hard commitment contracts in the context of physical activity. Because we randomised soft and hard contract offers, we can investigate whether (soft) contracts on their own help individuals achieve their physical activity goals, or whether having a hard penalty is a must. Importantly, recent research by John (2020), Carrera et al. (2022) and Bai et al. (2017) show that hard commitment contracts may reduce welfare in some cases because of the penalties imposed on those who do not reach their goals. It is therefore crucial to understand the role of financial penalties in the success of commitment contracts.

The hard contracts we investigate were self-funded, making the intervention highly scalable – and reflective of existing online commitment platforms like www.stickk.com. That people put their own money at stake is potentially important because individuals may behave differently when making decisions about their own money versus other people’s money and/or easily earned money (for instance money earned in an experiment). It is also possible that individuals experience a greater loss in utility when they lose their own deposited money compared to simply earning less from an experiment, which could impact their behavior in response to the contract (Kahneman & Tversky, 2013).

Finding ways that work to get individuals to be more physically active, and more generally to achieve their goals, is important both at the individual and policy-maker level. We find that commitment contracts can be effective in increasing physical activity even among current gym goers, who may be generally healthier and already priorities physical activity more than the general population. Importantly, it seems that a hard penalty does confer greater commitment contract success.

References

Bai, Liang, Handel, Benjamin, Miguel, Edward, & Rao, Gautam. 2017. Self-control and demand for preventive health: Evidence from hypertension in India. Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–55.

Bhattacharya, Jay, Garber, Alan M, & Goldhaber-Fiebert, Jeremy D. 2015. Nudges in exercise commitment contracts: a randomized trial. Tech. rept. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Cappelen, Alexander W, Charness, Gary, Ekström, Mathias, Gneezy, Uri, & Tungodden, Bertil. 2017. Exercise improves academic performance. NHH Dept. of Economics Discussion Paper.

Carrera, Mariana, Royer, Heather, Stehr, Mark, Sydnor, Justin, & Taubinsky, Dmitry. 2022. Who chooses commitment? Evidence and welfare implications. The Review of Economic Studies, 89(3), 1205–1244.

Erickson, Kirk I, Voss, Michelle W, Prakash, Ruchika Shaurya, Basak, Chandramallika, Szabo, Amanda, Chaddock, Laura, Kim, Jennifer S, Heo, Susie, Alves, Heloisa, White, Siobhan M, et al. 2011. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 3017–3022.

Fricke, Hans, Lechner, Michael, & Steinmayr, Andreas. 2018. The effects of incentives to exercise on student performance in college. Economics of Education Review, 66, 14–39.

Gerdtham, Ulf-G, Wengström, Erik, & Wickström Östervall, Linnea. 2020. Trait self-control, exercise and exercise ambition: Evidence from a healthy, adult population. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25(5), 583–592.

Himmler, Oliver, Jäckle, Robert, & Weinschenk, Philipp. 2019. Soft commitments, reminders, and academic performance. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(2), 114–42.

John, Anett. 2020. When commitment fails: evidence from a field experiment. Management Science, 66(2), 503–529.

Kahneman, Daniel, & Tversky, Amos. 2013. Choices, values, and frames. Pages 269–278 of: Handbook of the fundamentals of financial decision making: Part I. World Scientific.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2019. The Heavy Burden of Obesity. DOI

Roig, Marc, Nordbrandt, Sasja, Geertsen, Svend Sparre, & Nielsen, Jens Bo. 2013. The effects of cardiovascular exercise on human memory: A review with meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8), 1645–1666.

Royer, Heather, Stehr, Mark, & Sydnor, Justin. 2015. Incentives, commitments, and habit formation in exercise: evidence from a field experiment with workers at a fortune-500 company. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(3), 51–84.

Schilbach, Frank. 2019. Alcohol and self-control: A field experiment in India. American economic review, 109(4), 1290–1322.

Spika, Devon, Wickström Östervall, Linnea, Gerdtham, Ulf, & Wengström, Erik. 2023. Put a Bet on It: Can Self-Funded Commitment Contracts Curb Fitness Procrastination? Tech. rept. Lund University, Department of Economics.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Physical activity. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity on 2021-02-04.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Devon Spika

This research was undertaken as part of the author’s PhD studies at the Department of Economics at Lund University. Read more about the dissertation: Gender, health, the decisions we make and the actions we take