If a friend of yours told you they need to go to the doctor, most people would think about a doctor at a primary care practice (“Vårdcentral” in Swedish). There is a reason for this: In contrast to most other parts of healthcare, primary care physicians serve the whole population in a country and primary care practices tend to be the first place people turn to when they have a new ailment. Therefore, changes in the quality of healthcare in the primary care sector have the potential to affect millions of lives around the world (OECD, 2021). The quality of primary care can take shape in many ways: Did you receive the appropriate medication? Do you see the same doctor each time you go, or talk to a new person each time? Or, do you consistently go to the same practice each time? In this study, I focus on the last case, which tells us how important the continuity of care is between a patient and their primary care practice. Existing studies tell us that the continuity of care between physician and patient is important for patients (e.g. Simonsen et al., 2022, Staiger, 2021; Sabety et al. 2021), but less is known about how important continuity of care is in the context where patients are mainly attached to a practice and not a specific doctor.

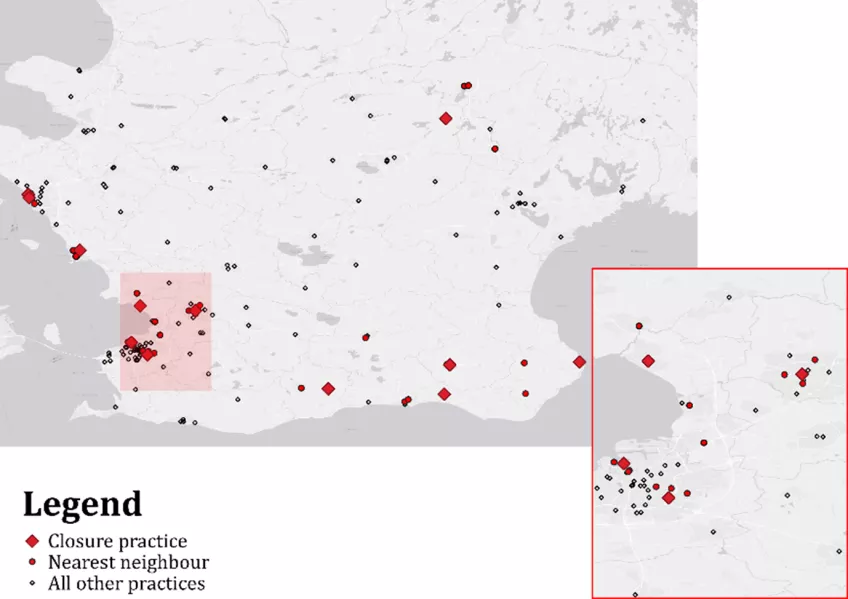

I study how patients’ healthcare utilisation is affected when they lose the possibility to see their regular primary care practice. I analyse the primary care utilisation and hospitalisations of patients who used to go to one of twelve primary practices in Region Skåne, Sweden that closed in 2009 to 2017. As a last step, I also analyse how the patients and total visits are affected in the neighbouring practices of closures. Figure 1 shows the location of primary practices in Region Skåne in my time period, and distinguishes between the twelve closure practices, their neighbours and all other practices. The map shows us that closures of practices occurred in both urban and rural areas, and all but one closure along the south or west of Skåne, which roughly corresponds to where most of the population lives.

It may seem like the most straightforward way to study how patients are affected by closures would be to follow patients whose practices closed over time. However, there may be other things that happen at the same time as the closure which might affect healthcare utilisation. One example is a pandemic, such as the Swine Flu or COVID-19 (Moynihan et al., 2021). Another example is if healthcare utilisation changes for everyone over time, such as fewer visits due to technological improvements. A simple pre-post analysis would therefore not be able to separate the effect of the closure and the general trend.

To circumvent this problem, I compare the outcomes of patients exposed to a closure to those of patients whose practice remained open in the same period. This approach allows me to correct the differences in outcomes for Skåne-wide trends. The observed difference in the change in healthcare utilisation and hospitalisations following the closure can then be attributed to the closure itself for the affected patients. To adjust for the possibility that patients in practices that close are different than patients in other practices – such as patients at closures being older and consuming more care – I focus on the relative change in healthcare utilisation over time, which allows for initial differences in e.g. the number of doctor visits. In Figure 1, one can think of the empirical strategy as a comparison of the change in healthcare utilisation for patients whose main practice closed (red diamonds) to patients in other practices (red and white dots). Similarly, the analysis of indirect effects on neighbours corresponds to a comparison of the changes in outcomes of patients at neighbouring and non-neighbouring practices (red versus white dots).[1]

I find that the closure of primary care practices leads to a 15% reduction in physician visits for the affected patients. This corresponds to about one in five patients opting to not see a doctor when they would have without being exposed to a closure. This effect is sustained for at least two years. The effect is the largest for patients with lower primary care utilisation and no chronic disease prior to the closure, suggesting that the biggest drop in visits occurred for patients with lower initial scope for continuity of care. One explanation to these results is therefore that patients with frequent contact with health services were more proactive or received guidance in finding their next primary care provider. For patients with less experience with healthcare, finding a new provider may be more daunting or difficult. I also find that there is a spillover effect on the neighbouring primary care practices. Neighbouring practices see an immediate influx of patients whose practice closed. This also leads to a reduction in visits for their earlier patients for up to a year, but it recovers to the pre-closure level two years after the closure. This dip in visits for patients can be interpreted as a temporary capacity constraint which lowered access to physicians while the practice adjusted to the higher demand.

The results of this study provide an important lesson to policymakers, in particular in healthcare systems that are amid or that have recently adopted a system of group practices in primary care. Group practices likely leads to certain advantages for patients, which includes a lower probability of a practice having to close following a doctor’s retirement or move. However, the potential benefit of this system comes at a cost: As evidenced here, group practices do close at times. When this happens, a relatively large patient population is displaced, and the local primary care market may have a bigger challenge in absorbing the patients that lost their primary care provider, than when a solo practice closes. In this context, it is therefore imperative that patients and remaining practices receive active guidance from policymakers, such as the region in charge, on how to accommodate the closure of a practice.

References

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2021), OECD Health Statistics 2021: Avoidable mortality, OECD reports and publications.

Staiger, B. (2022). Disruptions to the patient-provider relationship and patient utilization and outcomes: Evidence from Medicaid managed care. Journal of Health Economics, 81, 102574.

Simonsen, M., Skipper, L., Skipper, N., & Thingholm, P. R. (2021). Discontinuity in care: Practice closures among primary care providers and patient health care utilization. Journal of Health Economics, 80, 102551.

Moynihan, R., Sanders, S., Michaleff, Z. A., Scott, A. M., Clark, J., To, E. J., ... & Albarqouni, L. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ open, 11(3), e045343.

Sabety, Adrienne H., Anupam B. Jena, and Michael L. Barnett. 2021. “Changes in Health Care Use and Outcomes after Turnover in Primary Care.” JAMA Internal Medicine 181 (2): 186–194.

About the author

Linn Mattisson

This research was undertaken as part of the author’s PhD studies at the department of Economics at Lund University (Mattisson, 2023). The thesis includes two additional studies on health economics. One chapter examines the substitution between traditional in-person visits to doctors and video call consultations with a doctor for young adults in two Swedish regions: Västra Götaland and Stockholm. We find evidence that there is a partial substitution between these two types of services. The third chapter in the thesis studies the effect of waterborne diseases on children’s learning in Tanzania, finding that children are particularly vulnerable to waterborne diseases where sanitation is low and population density high.

Essays on the effect of health care and the environment on health

[1] Note that the map ignores the time dimension within my period of when practices operate. For example, in Lund in the top right cluster of the highlighted rectangle in Figure 1, it may seem that there is one practice that is even closer to the closure practice than the three red dotted neighbours, but this practice was not operating around the period the practice closure.